- Home

- Camille Bouchard

Hunting for the Mississippi

Hunting for the Mississippi Read online

Camille Bouchard

HUNTING

FOR THE

MISSISSIPPI

Translated by Peter McCambridge

Baraka Books

Montréal

Édition originale en langue française parue sous le titre Le rôle des cochons

© 2014, Éditions Québec-Amérique

Translation © 2016 Baraka Books

ISBN 978-1-77186-072-7 pbk; 978-1-77186-073-4 epub; 978-1-77186-074-1 pdf; 978-1-77186-075-8 mobi/pocket

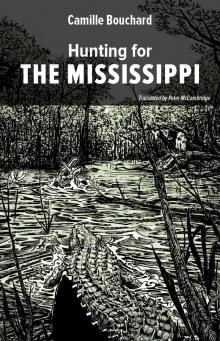

Cover by Folio infographie

Cover Illustration by Vincent Partel

Back cover photo: courtesy of Barclay Gibson

Book design by Folio infographie

Legal Deposit, 2nd quarter 2016

Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec

Library and Archives Canada

Published by Baraka Books of Montreal

6977, rue Lacroix

Montréal, Québec H4E 2V4

Telephone: 514 808-8504

[email protected]

www.barakabooks.com

Printed and bound in Quebec

We acknowledge the support from the Société de développement des entreprises culturelles (SODEC) and the Government of Quebec tax credit for book publishing administered by SODEC.

We acknowledge the support of the Canada Council for the Arts, which last year invested $153 million to bring the arts to Canadians throughout the country.

Trade Distribution & Returns

Canada and the United States

Independent Publishers Group

1-800-888-4741 (IPG1);

[email protected]

Contents

Reader’s Note

PART I

La Rochelle, 1684

1. It’s a Tough Life

2. The Fruit Beneath the Hoof

3. Going on a Big— a Very Big—Ship

PART II

At Sea

4. Work for Pigs

5. Speaking of Mr. De LazzzSalle

6. The Ceremony Under Threat

7. The Happiest Two Settlers

8. Raised Voices

9. Grey Splotches

10. Sailing Lesson

PART III

America

11. Naked Like Animals

12. On Dry Land

13. The Natives Attack

14. Thunder in the Blue Sky

15. The Birthday

16. Don’t Blaspheme

17. The Crocodile

18. The End of L’Aimable

19. Separation

PART IV

Royal Land

20. Hunting for the Mississippi

21. Savages and a Snake

22. The New Fort

23. Insulting Our Mothers

24. The Lame

25. The Sound of the Hummingbird

26. The Disappearance

27. Divine Impotence

28. Once Blue

29. The Cry of the Wolf

PART V

The Final Expedition

30. The Final Expedition

31. As Though He Knew

32. Crossing the River

33. Mr. De LazzzSalle’s Premonition

34. Back at Camp

35. Among Rebels

36. The Return of the Hummingbird

37. The Vengeful God

What Happened Next

About the Historical Characters

“In the name of Louis XIV, King of France and Navarre, on this, the 9th day of April, 1682, I, René-Robert Cavelier de La Salle, by virtue of His Majesty’s commission, which I hold in my hands, and which may be seen by all whom it may concern, have taken and do now take, in the name of His Majesty and of his successors to the crown, possession of the country of Louisiana, the seas, harbours, ports, bays, adjacent straits, and all the nations, peoples, provinces, cities, towns, villages, mines, minerals, fisheries, streams, and rivers, within the extent of the said Louisiana.”

Ceremony founding Louisiana,

a milestone in the history of New France

Reader’s Note

This novel is based on fact. The violence and horrors experienced by the characters were the lot of many explorers of the time and were not dreamed up by my imagination.

The term “savage” should not be given the negative connotation it has today, and at the time the term simply meant “woodsman.” However, the word “Indian” is bound to an historical mistake attributed to Spain’s first colonizers. I have therefore avoided using the term, except in dialogue.

C. B.

PART I

La Rochelle, 1684

1

IT’S A TOUGH LIFE

My mom’s been wearing the same dress for months. Come to think of it, she’s been wearing it ever since the fever took my father. It’s not her way of showing she’s in mourning: it’s because she has nothing else to wear. From time to time, at dusk or dawn, she undresses by the sea in the dark. She gives the dress a good scrub, before putting it back on, still wet. That’s fine in summer, but in winter…

My little brother Armand is five years old. He and I prefer not to wash. We’re covered in lice and fleas, but at least we don’t freeze. And now my younger brother is coughing all the time. Sometimes he doesn’t sleep at night. He’s even started spitting up blood. So there’s no way he’s going to get his clothes wet either.

Poor and hungry, the three of us live in a hovel in La Rochelle, France.

In a big town like this, with no family or friends, a widow with two children has barely anyone to turn to. Unless she has a little money set aside.

Mom doesn’t have a cent. She doesn’t have any friends to speak of either.

From time to time, on the way out of mass, passersby hand us a crust of bread, a half-eaten piece of fruit, a handful of chestnuts, or if we’re lucky, a coin. Armand and I sing to attract more sympathy. We sing badly, but we sing all the same. It doesn’t bring in much, but now and again we’re happy enough.

“Such lovely children!”

I hate adults running their hands through my hair like that. It’s not so much what they do as why they’re doing it that upsets me. No one thinks I’m twelve; everyone thinks I’m younger. Much younger. I’m not tall or stocky, not by a long shot. And that comes in handy for Mom as she looks to attract the sympathy of onlookers. But I can’t stand looking like a little kid! I’m almost a man, for heaven’s sake!

I cross myself quickly. I’ve just sworn outside the church.

“Aagh!”

The shriek comes from Mom, who is sitting on the ground. At first I think she’s shrieking at the shiny copper coin the parish priest has just slipped into her palm. Then I see that the same priest, still leaning over my mother, has grabbed one of her breasts.

“If you’re looking for more money, Delphine, leave the two kids here and come into the sacristy with me.”

And the priest ruffles our hair before striding off toward the door at the side of the church. His long Franciscan robe whips up the filth of the street as he walks. The hem is stained with dust and dog poop.

My mother, still on the ground, looks at the coin, then at my brother, at me, at the coin, my brother… She seems to be thinking hard. She half turns toward the priest, who has disappeared into the church through the sacristy door.

Mom stays where she is, thinks things over a little more, then bursts into tears.

Life, for a widow, can be tough.

* * *

“Hey, Stache. How�

�s it going?”

My name’s Eustache. Eustache Bréman. I don’t really know why, but Marie-Élisabeth Talon has taken to calling me “Stache.” In different circumstances I think that would drive me mad. But I’ll forgive Marie-Élisabeth Talon anything.

Anything at all.

“Wanna go draw on the beach with Armand, Jean-Baptiste, and Ludovic?”

She always treats me like I haven’t even already turned ten or, worse, as though I was the same age as Pierre, her brother, who’s two years younger than her!

But I forgive her. Because of her blue eyes. Because they remind me of the sea around the Island of Ré. Because they remind me of blueberries in the summer sun. I also forgive her because of her thick, wavy hair and the long brown locks that frame her perfect face.

I hold nothing against Marie-Élisabeth Talon because I’m in love with her. Totally, irreparably, infinitely in love with her. She is ten years old and I am twelve. We are made for each other, I’m sure of it.

Aside from the fact that she has no idea.

“Did you see the big fish Jean-Baptiste drew? I’m sure you could do better.”

Curse this scrawny little body of mine! Curse my body of a child! I have the mind of an adult.

“I’m twelve, you know, Marie-Élisabeth. I have no time for playing with your brothers like little kids.”

She frowns a little, but doesn’t look at me. Instead she keeps an eye on the rabble of kids as they run around.

The Talons have five children. Marie-Élisabeth is the eldest. Then there’s Pierre, who’s eight. Then Jean-Baptiste, seven, Ludovic, five, and Madeleine, four. All with blueberry eyes. Like Mr. and Mrs. Talon.

“You look younger,” she replies eventually. She’s not being mean, just explaining why she thought I might like to play with the kids.

“I’m twelve. Old enough to be going out with you.”

She laughs. Still doesn’t look at me.

“I want to go out with you, Marie-Élisabeth.”

She laughs. Still doesn’t look at me.

* * *

My mom and Mrs. Talon are friends. They know each other, I mean. I don’t know any longer if Mr. Talon was close to my dad, but the women say hello to each other when they meet, talk about women stuff, laugh over the occasional shared joke… One time Mrs. Talon even gave Mom a loaf of bread.

“Come on, Isabelle,” my mom protested. “You have five kids. I can’t accept this.”

“But I have a husband, Delphine. Who works. We don’t always eat our fill, but when God gives us a little more than we need, it’s to help those worse off than ourselves.”

Any food we manage to get is always for my little brother first. Mom and I make do with what’s left over.

Or that’s how it is until he dies. And the sad thing that day is that even though we get his portion, we don’t have much of an appetite.

As we watch the gravedigger bury Armand, Mom holds me tight and cries. She cries really hard. And she holds me really tight. I should be the one consoling her, clutching her to my chest. My manly chest that looks like a child’s. In Mom’s eyes, I’m still a little boy. And I have to admit that as I watch my younger brother disappear into a big hole that is covered with lime, I feel very little.

Very little indeed.

2

THE FRUIT BENEATH

THE HOOF

“You can’t imagine how huge the country is.”

My heart is crushed like an over-ripe fruit beneath a horse’s hoof.

“You can walk for weeks—weeks, Delphine!—without meeting a living soul. Nothing but forests and lakes filled with the purest water.”

Mrs. Talon, her husband (his first name is Lucien), and my mom are sharing a watered-down cider bought on the cheap from a peddler. Their three youngest children are sleeping on the straw mattress they share as a bed. Pierre and Marie-Élisabeth are off in the corner, shelling dried peas they got who knows where. I’m standing next to my mom.

“It sounds heavenly,” Mom replies, with a dreamy look that can be heard in her voice. “So much so… so much so that it seems impossible.”

“It’s not so simple, it’s not that easy,” Lucien Talon retorts. “You need to provide your own food, whether that means sowing seeds, picking berries, hunting, or fishing, and the Savages are best avoided, but there’s so much space… Life there…”

“So many animals, Delphine. Deer, hares, partridges… So many birds that they mask the sky like huge storm clouds. So many fish that you could walk across the waves.” So many this… so many that…

As she reels off all the wonders, I think to myself that my love alone, no matter how intense, will never be enough to convince Marie-Élisabeth—let alone her parents!—to stay. To decide not to return to this America, where they have already lived, and whose marvels they are keen to share with us.

What will I do once the Talons are aboard the huge ship come to take them away? How will I bear to watch the setting sun, knowing that on the other side of the ocean it lights up the afternoons of the girl I love?

No longer an over-ripe fruit, my heart has become a dried pea that Marie-Élisabeth is shelling without a shred of emotion.

“Isn’t there a terrible winter in this country of yours?” Mom asks, drumming her index finger on her bottom lip.

“Only in Canada,” replies Mr. Talon, his irises resembling two big drops of blue sea water that have fallen into his eyes. “At Québec, where we got married, we’d never been so cold in our lives. But not in Louisiana. It hardly ever freezes there. At least, not like here, and much less than in Canada. Aside from a few winter nights, the weather there is mild and warm.”

“And,” his wife chips in, leaning over the table to take Mom’s fingers in her own, “the king will shower all kinds of privileges on the first baby born in the colony. Titles, a seigneury…”

“A seigneury?” splutters my mother. “And you’re planning on having another baby over there?”

Mrs. Talon steps back to rest her hands on her belly. “It’s already on its way,” she says, her voice barely a whisper.

I instinctively turn to Marie-Élisabeth and Pierre. Do they know they will soon have a new little brother or sister?

Either they didn’t hear or they already know because they don’t react. When I look back at my mother, even from my angle, I can see her jaw drop.

“You’re expecting?” she finally manages, pronouncing each syllable slowly.

“We’ve counted the days,” Lucien Talon replies, “and if the crossing isn’t delayed, our child will be born in Louisiana.”

The man clutches his wife’s hand and holds it for a moment. The four drops of seawater of their irises blend together in a display of everlasting love. So much love, in fact, that my heart is torn a little more.

I no longer dare turn to face Marie-Élisabeth and I don’t feel like exchanging glances with my mom either. Mom is staring at me now, but I know it’s less about looking at me and more about averting her gaze from the couple. Because she still misses Dad. Like I will miss Marie-Élisabeth.

“Why don’t you come, too?”

It takes a long while for me to get my head around Isabelle Talon’s question to my mom.

“To… America?” she stammers after a moment’s hesitation.

“Of course!” says Mr. Talon. “The leader of the expedition—”

He breaks off. “It will be René-Robert Cavelier de La Salle. His Majesty has just appointed him governor of Louisiana. And Mr. De La Salle will be only too glad to see you. Of the three hundred people set to go on the expedition, there are only a handful of women. How will we ever establish a colony worthy of the name if there aren’t enough women for the men who wish to stay and start a family?”

“But I’m a widow!”

“Precisely, Delphine!” says Lucien Talon ent

husiastically. “You are free to take a second husband. A new father for Eustache, you’ll have some more children, replace the one you… I mean, the one who…”

“You’ll be able to eat every day,” Isabelle Talon interrupts before her husband mentions Armand. Every time Mom hears his name she bursts into tears. “It’s not like here, Delphine. You won’t have to go begging for bread. You’ll be able to bake your own, and who knows, maybe bread for the rest of the village.”

Mom bursts out laughing as though she’s just heard the best joke ever.

“Come off it!” she gasps. “Can you really see me with… with another husband?”

“Why ever not?” retorts Lucien Talon, turning serious. “You’re still young, Delphine, and—if I may—a very beautiful woman. The men on the expedition will be falling over each other to have your hand. The paradise we’ve been telling you all about can be yours too.”

I feel a sharp pain coming from the knuckles on my right hand. Mom has grabbed hold of my fingers without realizing just how hard she is squeezing. It’s less as though she’s considering the offer and more like she’s holding on to a mast or rope to keep her feet.

My heart—my flat, saddened heart—swells when I notice Marie-Élisabeth staring over at me. Like she’s trying to read my mind, to find out if I’d like to go with them. Or to mentally sway the decision that is Mom’s to make.

Intimidated, I look back at my mom. I almost jump when I see how she’s looking at me.

“Eustache…”

“Mo… Mom?”

“Would you be scared of going on a big—a very big—ship?”

I mull over the answer in my head, but try as I might I can’t put into words just how strong my desire is to leave with Marie-Élisabeth Talon. My heart is now as strong as a horse’s hoof crushing a ripe fruit underfoot.

3

GOING ON A BIG—

A VERY BIG—SHIP

The first time I set eyes on Mr. René-Robert Cavelier de La Salle, we are already on the quay. We’re getting ready to board the ships chartered for the expedition. He is very busy as he approves every detail the captains, quartermasters, clerks, and officers bring to his attention. Documents are brought to him, and approved with a brusque nod; gentlemen and priests are introduced to him, and greeted with a brusque nod; and various things on the boats are pointed out to him, and approved or turned down with a brusque nod or shake of the head.

Hunting for the Mississippi

Hunting for the Mississippi